Local artist captures blight, graffiti with photos | News, Sports, Jobs

Staff photo / Andy Gray

Carl Henneman of Warren draws inspiration from abandoned area structures and the graffiti that covers them for his photography.

WARREN — Carl Henneman finds beauty where most people see blight.

Much of the 45-year-old photographer’s work focuses on abandoned, deteriorating buildings and the graffiti that often covers them.

“There’s kind of a hauntedness to it,” he said. “I see all these places that were once so loved and lived in, and now they’re abandoned to where they mean nothing to anyone. I kind of feel, I don’t want to say an obligation, but I just feel compelled to document these things before they are torn down.”

Photography wasn’t his first choice for creative expression. He always was interested in artists and writers growing up, but he described his paintings as “horrendous.” He considered screenwriting, but soon realized the long odds of success in that field.

Henneman said he wrote two volumes of poetry, “but after doing poetry for so long, I started feeling my work, personally, was just a lot of hot air.”

Then he got his first digital camera and started experimenting with manipulating the photos he took.

“I saw a way in with digital manipulation. It seemed like painting to me, working with light, capturing light. I saw a lot of similarities there and just went with it.”

Henneman credited James Shuttic, director of the Fine Arts Council of Trumbull County and an artist / photographer, as being a huge influence on his development. Through Shuttic, he met like-minded artists and other people in the local arts community, and he had an opportunity to show his work at downtown Warren’s Art on Park building and local galleries.

William Mullane, gallery director at Trumbull Art Gallery, also played an important role by picking Henneman in 2015 as one of six photographers to document brownfields — properties where their reuse or redevelopment could be complicated by the presence of hazardous substances, pollutants or contaminants — in Trumbull County. Henneman photographed the site of the former St. Joseph Riverside Hospital on Tod Avenue NW.

“That was insane going in there,” he said. “It was a biohazard. I had to wear a respirator on the lower levels because they were flooded, there was black mold. You’re seeing mattresses in there with heroin and drug items strewn everywhere. You could just imagine what was going on in the building, and it was in such disrepair.”

The response to that exhibition showed Henneman there’s an interest in this kind of work.

One of the perks of the brownfields exhibition is it gave Henneman access to a site he never could explore — at least not legally. Henneman admitted to jumping the occasional fence to get to a place he wanted to photograph, but he’s never run into any serious problems.

“I’ve gone to places where I’ve been approached by security guards,” he said. “I’ll talk to them, let them know I’m artist, pull up my Instagram page (@zenstreetart) and show them I’m not here to steal copper, I’m actually a photographer. Nine times out of 10, they’ll tell you, ‘You should get a picture up behind this loading dock,’ and they’ll go with me, tour it and see me out.”

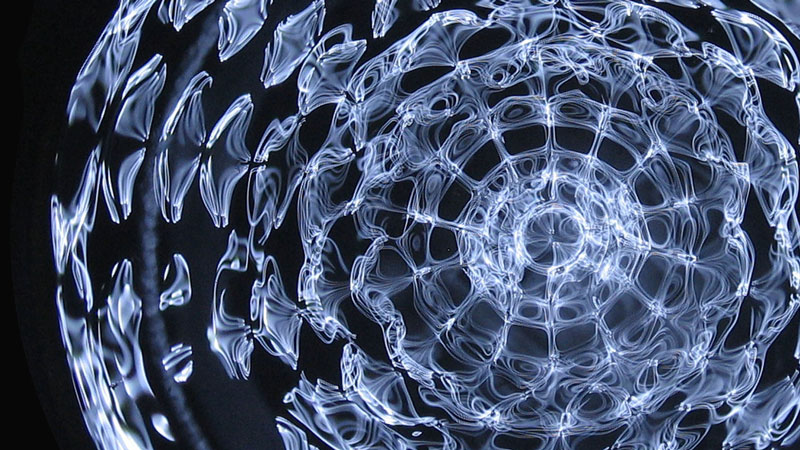

In recent years, he’s been drawn to the graffiti that covers many of these sites. He loves the collaborative part of graffiti art, how one artist will alter and expand upon the work that’s already there, and by documenting it he preserves its evolution.

Those photographs also combine his love of both art and writing. He talked about a recent trip to a graffiti-covered observatory in East Cleveland. Spray-painted on one surface was the line, “It’s no surprise you turned out this way.”

“It just hits you like a ton of bricks,” Henneman said. “I couldn’t sit down and write a 40-line poem saying it better. It was just perfect. I also like that it’s coming from people in that area that have lived and experienced this. There’s no intellectual pontificating about it. It’s just this raw emotion.

“Then you add in the dynamics of color usually included with graffiti. I like to use selective color, make that graffiti pop and everything else I’ll push back. I love playing with photos like that, and graffiti really provides me that opportunity.”