NFTs: Digital Art’s Latest Trend Makes Its Way to Central Illinois

An Internet buying frenzy of digital arts and collectibles this spring marked a debut for NFTs, or non-fungible tokens.

At its most basic, an NFT records ownership and transactions. They are certificates of authenticity for the virtual world, tied to digital assets — such as image, music and video files.

Central Illinois digital artists are watching the format’s rapid rise in popularity, with some joining in.

Though around for several years, NFTs seemed to come from nowhere earlier this year — taking over podcasts, news articles, even a Saturday Night Live sketch.

NFTs – SNL

And there’s money in it, too. After a first quarter in which NFTs cleared $2 billion in sales, they now are slowing. But, as recent weeks have shown, digital market volatility is such a given, it makes predictions a toss-up.

Kimberly Babin Marshall, McLean County Arts Center project coordinator, attributes NFTs’ rapid rise to growing interest in crypto finance and arts, but also to a year of pandemic that found galleries closed and people in lockdown. She said word got around about the new technology.

Babin Marshall, a painter and photographer, said novelty also is part of the NFT attraction.

“They’re also purchasing a piece of history. When photography evolved, you could get a color portrait instead of a tintype. People wanted to own that, and they wanted to experience it,” she said.

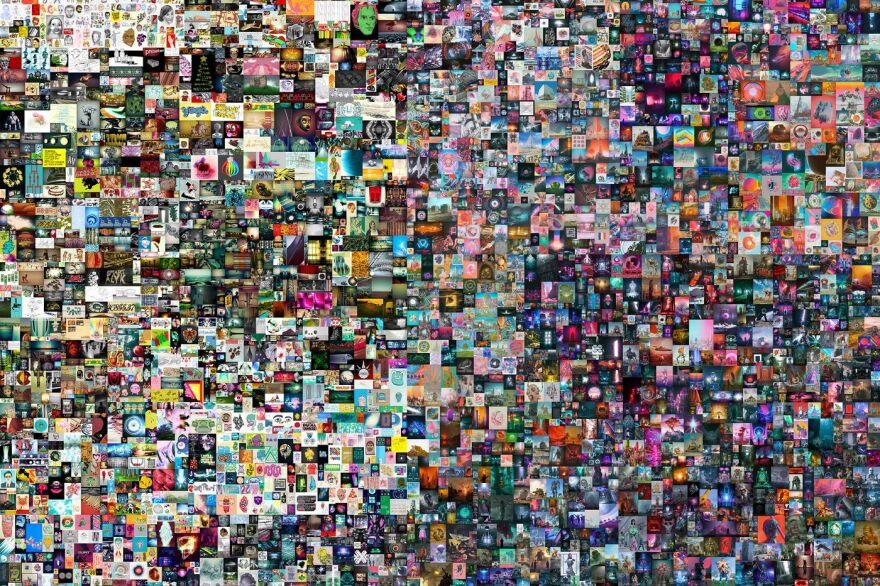

In mid-March, Christie’s auctioned Mike “Beeple” Winklemann’s NFT “Everydays: The First 5,000 Days” for a record $69.3 million. Some say Christies’ involvement gave a stamp of approval to the burgeoning field of digital arts.

Though it’s been around since the 1980s, it’s grown in recent decades in step with the increasingly digitized world at large.

Rick Valentin, a Bloomington-based musician, has released his own set of multimedia NFTs through his solo project, Thoughts Detecting Machines.

Valentin called the Beeple sale an example of how NFTs are disrupting the concepts of value and ownership.

“I can get a copy of the $69 million digital artwork right now and I can put it on my screensaver?—Yeah, you can. But you don’t own it, right? Somebody else paid $69 million dollars for the idea that they own it,” said Valentin.

The parameters of NFTs keep expanding. This spring brought a $3 million NFT of an image of Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey’s first tweet; and half million here and there for famous gifs, and memes. The famous Nyan cat animated gif sold for almost $600,000;

There are “experience” NFTs, to jam with celebrity musicians; ones tied to real-life objects, like houses and cars; and even one created by AI-celebrity, Sophia the Robot.

NFTs of sports collectibles also are popular, especially with NBA’s Top Shot marketplace, offering video-clip NFTs, akin to real-world baseball cards. Top Shot’s trajectory has mirrored the wider NFT trends.

How do NFTs work?

NFTs are smart contracts, self-executing applications built on the digital, decentralized ledger known as the blockchain.

Bitcoin arrived in 2009 with the blockchain as the technology behind keeping its records — across many, many computers.

Those first-gen cryptocurrency coins, like Bitcoin, are fungible, or equal. Think $1 for $1. But non-fungible tokens hold unique values that can be changed with each resale, plus unlock a unique file.

Illinois Wesleyan University finance professor Jaime Peters explained this cryptocurrency evolution: “It does the same type of thing. But inside of that data block I can also put other types of data,” said Peters.

But Shaoen Wu, the State Farm Endowed chair of ISU’s cybersecurity program, said sometimes people confuse the NFT for the artwork, or for the money to buy it. The smart contract is built into the coin, most commonly an Ethereum coin, also called Ether.

“Digital currency is more related to, like, currency money. But the NFT is not the actual thing itself, but proof of the ownership of the transaction,” said Wu.

History of new media trends

Valentin has a history as an early adopter of new technologies.

As a computer programmer, he helped pioneer enhanced CDs. He and Poster Children bandmate Rose Marshack, a fellow creative technologist to whom he’s married, have co-hosted their podcast Radio Zero since the 1990s — long before podcasts became a household word.

So, it’s no surprise he’s also been following NFT development since its beginnings.

Back in 2017, when he was teaching one of his graduate seminars on arts and culture, he learned a pair of fellow NYC-based creative technologists were doing an experiment with blockchain technology.

The Larva Labs duo had created a limited set of 10,000 pixelated images, with various programmed attributes. These were free for the taking. All one needed was a digital wallet, and to pay the Ethereum network gas fees. On a whim, Valentin grabbed one — something fun he thought.

A few weeks ago, Christie’s auctioned a set of nine of those CryptoPunks — now considered the prototypes of NFTs — for $17 million. Christie’s described the NFTs as “a paradigm-altering model for the digital art market and a challenge to the concept of ‘ownership’ itself.”

Valentin said those pixelated images are seen as the first digital tokenized artwork. People didn’t buy the image, but rather a pointer to it.

“I wasn’t really interested in making millions of dollars off of Bitcoin. That seemed like gambling, or you know, playing the stock market. But all of a sudden when this CryptoPunks project happened, that’s when I sat down and went through the whole process,” he said.

He started to imagine how artists might tinker with building digital culture.

Valentin’s NFT project combines music, art

TDM-NFT is a cross between traditional songwriting, and programmatic work, and reflects on that journey: Valentin said it’s a nod to conceptual art, and reflects the interwoven blockchain.

Each of the 100 NFTs is a multi-instrumental, programmed loop of a puzzle incorporating patterns, instruments and vocals tied together. Each buyer gets a connected, one-of-a-kind digital artwork. He described them as connected and unique simultaneously.

He’s priced his NFTs at .001 of Ether at the marketplace opensea. Depending on the market, the exchange rate varies. These days that’s usually between $20 to $35. Crypto gas/mining fees are extra, and depending on the platform’s traffic, fluctuate widely. Often, the fees could double that price.

He’s also produced a related tutorial. One section gives a glimpse into the artistic process of his TDM-NFT project. But first he goes over NFT basics, and offers a brief lesson on the Ethereum blockchain where most NFTs are bought and sold. Then he offers a step-by-step to opening digital wallets.

“I really believe to be a creator in the 21st century you have to understand the technology, not just use it,” he said.

TDMNFT: 100 Unique Song Arrangements and Artwork by Thoughts Detecting Machines

Some artists take cautious approach

Normal-based digital artist Sean Thornton, an ISU graphic designer who also creates pop culture fan art, said like many people, he just learned about NFTs this year as pop culture made them a talking point on late night shows and among his coworkers.

He said he’s fascinated by the way NFTs seem to have created an instantaneous seed-change in the digital arts world. But in the rush to take part, he hopes fellow artists slow down and research their rights in the digital markets. For now, he’s holding off until he better understands the process.

“I’d want to learn how much rights I’d be giving away” if selling an NFT, he said. If he sold one of his artworks as an NFT, who would own the source file, for example, he asked.

He’s not alone. Ryan Bliss, a digital artist from rural McLean County, said he remains on the fence about NFTs as well.

His Digital Blasphemy online gallery already has nearly 20,000 international subscribers, with reserved access to his 3-D screensaver images. So, he wonders if creating NFTs, especially with the wildly fluctuating transaction fees, would be worth it.

An Artnet article following the spring hype around NFTs shared that despite the headline-grabbing million-dollar sales, more than half of NFTs sell for less than $200. Depending on gas fees to create the NFT, an artist could possibly lose money in the deal.

Plus, Bliss raised the sustainability concerns with blockchain processing. That’s been getting much more attention since Tesla CEO Elon Musk, a big crypto investor and influencer, has been vocalizing support for green reforms within the industry.

But for now, the energy consuming crypto-mining is the main method of moving NFTs and other digital assets.

“I think I’ll be a lot happier getting on board with it when these issues are ironed out,” said Bliss.

ISU’s Wu said holding back isn’t a bad idea. While blockchain has merits — like authentication, and immutability — it’s still young, and NFTs are “in the baby stage.”

The industry is rife with bad actors, too, said Bliss. Ransomware, money laundering, and con artists make the whole scene messy, he said. Earlier this year, Bliss’ attorney found someone trying to sell a Bliss 3-D digital image as his own NFT on an NFT Marketplace.

But Thornton noted even before NFTs, he’s run into issues with others trying to pass off his work as their own. This is just a new platform, he said.

Babin Marshall, who’s studying art law online with Christie’s, said this spring someone tried to sell an NFT of a Jean-Michel Basquiat drawing — with the promise the buyer could also destroy it. But it may have been a stunt to draw attention to the format’s existing loopholes, she said. It’s true NFTs have many untested legal questions, she said. Some categories that came to her mind immediately were artists’ rights, copyright, intellectual property, and licensing issues.

But there’s potential too, she said. For example, NFTs’ smart-contract technology includes ways for artists to cut out a “middle-man” and to reserve a percentage of each NFT resale.

“It’s also just kind of a fun and exciting evolution of the human experience, and the different ways that we’ve adapted,” she said, noting new digital arts’ technology often is met with hesitancy.

She recalled not wanting to give up her music CDs, but now enjoying the convenience of connecting her phone to the car’s Bluetooth, and having a broad catalog accessible through her phone.

Valentin said artists are right to worry about their rights, volatile digital markets, and the climate issues of cryptocurrency mining. But he thinks working from inside is the way to address those.

“It’s really still the Wild West. And so we have lots of opportunities to kind of define that, and that’s why I think it’s important for artists to understand this and to start participating, and start having a voice in how these systems are built,” he said.

Plus he said not all digital collectors are speculators.

On a smaller scale, buying a digital artist’s NFT is just showing support. In the physical world, when we buy an artist’s record or painting, it’s because we like what they’ve done, he said, adding the same can be true with NFTs.

He said NFTs are the latest technology making our culture pause and reconsider ideas we take for granted.

“We have these preconceived notions about ownership. But the digital world has really disrupted those. As artists — but t

hen also as fans or consumers of art — we need to work out that relationship, and have these new understandings,” he said.