Nick Cave Digs Deep, With a Symphony in Glass

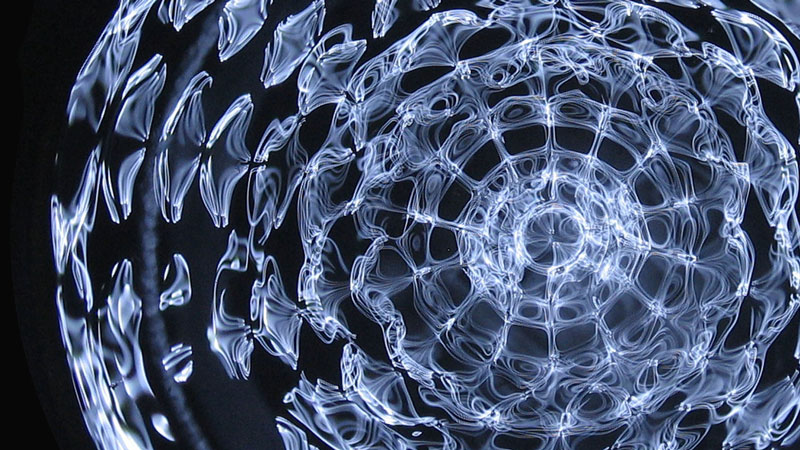

On a blistering afternoon in late August, a devoted crew of design workers moved by the corridor connecting Occasions Sq. and Grand Central Station, property to the 42nd Street Shuttle. Listed here, less than the streets of New York, about two dozen figures built of lively glass danced along the subway partitions.

On Friday, M.T.A. Arts & Structure will officially unveil “Every One,” the initial of a three-piece set up by the artist Nick Cave, within the new 42nd Avenue connector. The other two areas — “Each One” at the new shuttle entrance and “Equal All” on the centre island system wall — will be mounted next year.

The $1.8 million funds for the project, commissioned by M.T.A. Arts & Layout, is aspect of the overall venture to rebuild and reconfigure the 42nd Road Shuttle, which cost more than $250 million.

Cave — a sculptor, dancer and functionality artist — is identified for his Soundsuits, wearable material sculptures manufactured of resources these as twigs, wire, raffia and even human hair that often crank out sound when the wearer moves. (He’s also no stranger to staging artwork in train stations: In 2017, he brought a herd of 30 vibrant lifetime-dimensions “horses” to Grand Central Terminal’s Vanderbilt Corridor.)

Going for walks together the new and improved corridor, figures on the wall are depicted leaping and twirling in mosaic Soundsuits.

“It’s practically like seeking at a film strip,” Cave explained in an job interview from his studio in Chicago. “As you’re transferring down that from still left to suitable, you see it in movement.”

Considering the fact that the sculptor was chosen from a pool of artists in February 2018, he questioned and fearful: How would a dynamic, flowing Soundsuit transition into a static mosaic? He was relieved by the response: Seamlessly.

When Cave came to New York to see “Every One” in early August, he reported, “I felt like I was in the center of a overall performance, up near and own.”

“You just felt this rapid, different, visceral texture,” he extra, “the feeling in the motion and the move of the product that entirely resonated.”

The Soundsuits have constantly been an amalgam of cultural references, Cave discussed: the ideas of shamans and masquerade, obscuring the race, gender and course of the wearer and forging a new id. They contain ties to Africa, the Caribbean and Haiti.

“It’s really vital that you can make references, you can hook up to something,” Cave mentioned. “In one particular of the mosaics in the corridor, there’s a sneaker. So that delivers it to this urban, right-now time.”

From beneath a pink-and-black cloak of raffia, meticulously crafted out of glass shards, pokes a present-day sneaker in shades of salmon, white and maroon. Cave likes the participate in that is happening below: The variety is at times figurative, often abstract. “Sometimes it is identifiable and from time to time it’s not,” he said. “But that is the attractiveness of it all.”

Cave established his mosaic from recomposed source photos of the Soundsuits in movement shot by James Prinz and interpreted in glass. After completing the structure for “Every One” in early 2020, he picked the fabricator Franz Mayer of Munich from a list supplied by M.T.A. Arts & Design and style. His company, Mayer of Munich — a single of the world’s oldest architectural glass and mosaic studios — recognized Cave’s vision.

Mayer of Munich has been in the family of Michael Mayer, its present-day running director, for generations. (Michael is Franz’s terrific-grandson.) When the German fabricator will get to know the artist and their point of view, the team can translate the scanned layouts of the operate into a mosaic.

The artists, Mayer mentioned, “they’re the individuals with the magic.”

The fabricator prints out the types to-scale, lays them out on a desk and works on major of them. Cave’s unique mosaic was finished in a beneficial location strategy, which means the glass items were being glued straight onto a mesh backing — fairly than generating the style backward, like a mirror picture.

“What is the stone that goes to the next, and creates a selected symphony?” Mayer said about the process. His team lower the glass items, applied them to mesh mats, and then the mosaic slowly and progressively grew outward. The finished piece actions about 143 ft on just one side and 179 toes on the other, damaged up by 11 electronic screens in the middle. For 3 out of every single 15 minutes, all those screens will participate in videos of dancers undertaking in Soundsuits.

Shortly just before the shutdown, Mayer frequented Cave in his studio in Chicago. Then the artist arrived to see the operate in progress in Munich.

While this represented Cave’s initial time doing work with mosaics, he is now much more than interested in applying the medium again.

“I’m imagining about mosaic as sculpture — not that it’s just on the partitions, that it exists in house that you walk all-around the function,” Cave claimed. “So yeah, I’ve been thinking about it because I walked into that space.”

And at 42nd Street, his work will keep business with giants: Jacob Lawrence’s “New York in Transit,” Jack Beal’s “The Return of Spring” and “The Onset of Winter season,” and Jane Dickson’s “The Revelers” are all gl

ass mosaics in the Occasions Sq. station.

Roy Lichtenstein developed his “Moments Square Mural” in porcelain enamel. And Samm Kunce’s “Underneath Bryant Park” is a mosaic produced of glass and stone.

“Times Sq., it is the heart of the globe, of the region,” Cave said.

Sandra Bloodworth, the longtime director of M.T.A. Arts & Structure, emphasised the artist’s focus on other artists.

Cave is, she stated in an job interview in Bryant Park, “an artist who cares about individuals, who is so linked to community and so linked to people’s feelings.”

To have an artist who is “grounded in that be the do the job that we’re going to see as we return,” she continued, “as everyone arrives back and the town revitalizes, the timing is just completely great.”

“Every One” is all about motion, Cave mentioned. The glass dancers in their raffia and fur Soundsuits mirror the hustle and bustle of the additional than 100,000 persons who rode the 42nd Street Shuttle day by day before the pandemic — up to 10,000 riders per hour.

On that blistering day in late August, the movement captured on the walls matched what was occurring along the corridor underneath building. A guy in a hard hat sliced by stone in the center of the hallway with a h2o-jet cutter. Yet another gentleman carefully polished the freshly put in mosaic with glass cleaner and steel wool. Sweat dripped and staff buzzed around, creating new tracks.

“We are not only spectators,” Cave stated, “but we’re also component of the efficiency.”