On the Deal with: Dustin Yellin | January 2021 | Visual Art | Hudson Valley

Dustin Yellin is a madman. Very virtually. In 1999, the artist had a psychotic episode that led to Yellin’s incarceration and hospitalization. The craziest bit of it is that Yellin filmed it as it was going on, documenting his travels across Manhattan over the system of a weekend right before the NYPD arrested him. You can watch the film, The Crack-Up, on his web site.

Twenty several years on, Yellin is clearly nevertheless mad, but in the boundary-obliterating way that innovative geniuses are. A restless youth and a large university dropout, Yellin was drawn to artwork for its deficiency of constraints. “Artwork felt like the factor that had no partitions around it,” Yellin says. “Even prior to I examine or learned about artwork record, and had any references definitely, I was like, very well, this is infinite. This is fucking unlimited. And that felt extremely harmless.”

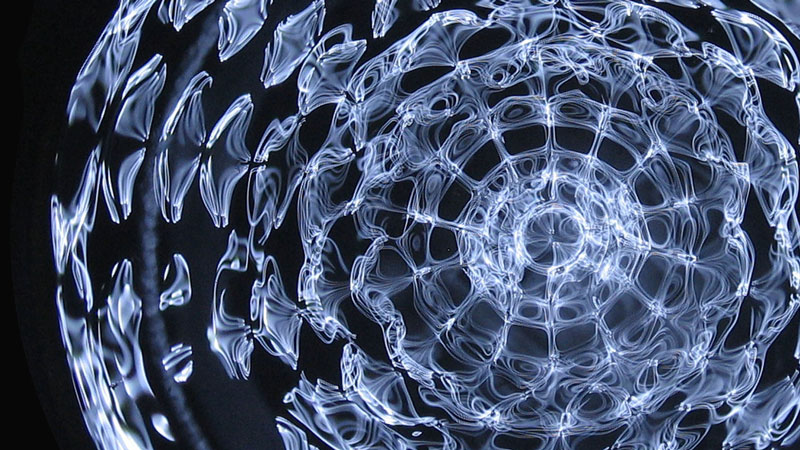

Some thing that was not safe was Yellin’s early function, a series of resin-based parts that observed him encasing crops and uncovered objects in resin, which is harmful. “I was heading to die,” he states. This led Yellin to glass-dependent is effective, like this month’s go over, The Theia Hypothesis, section of his Psychogeography collection, which will eventually consist of 120 pieces (about 100 have been fabricated currently). “Frozen cinema” is how Yellin refers to these pieces, in which he embeds hundreds of pictures clipped from publications and artwork publications in among wherever from 12 to 50 levels of glass. (The Theia Hypothesis is composed of 28 levels.) These will work, crammed as they are with the detritus of civilization, are not only maps of human consciousness, but also a societal archive. “I like the thought that if you can find a fallout, and this issue, you explore this thing, and you unbury it, you could study so significantly about our civilization from the past 1,000 decades,” says Yellin.

His hottest twist on telling a meta-narrative about humanity by means of hundreds of mini tales is a nine-foot-tall bronze sculpture he’s in the system of creating. “I am imagining about it as the last human,” Yellin says. “It will be produced of many, numerous objects, and manufactured of landscapes and dreamscapes, and volcanoes, and animals, and disparate pieces of clocks, and bottles, and frogs, and cash, and architectural aspects and cosmological fucking charts, and serious gay poems that are hidden, and fucking perhaps I am going to get Nelson Mandela’s shoe.”

One more ambitious challenge Yellin is functioning requires tipping a 1,000-foot-lengthy oil tanker vertically into a harbor. Site visitors would be equipped to go up and down the tanker in elevators, and then check out the observation deck. Yellin claims all proceeds from the exhibition—which would total an estimated $50 million a year—would go toward funding conservation projects. It would be termed The Bridge, to stand for the bridge from the previous to the long run of how we use strength. When questioned how near the project is to completion, Yellin suggests, “It was awesome how near we bought ahead of COVID, and then COVID just froze everything.” He’s coy about when and where The Bridge will come about, but Yellin says he has the engineering and funding sorted out.

When Yellin and I spoke in mid-December, he was at his Brooklyn studio, even though he was eager to get again up to his property in Putnam County, in which he’s building a sequence of earthworks influenced by Japanese Zen gardens. When questioned if there’s any distinction amongst doing work in the studio or out in the woods, Yellin demurs. “It’s all the exact. I you should not know how it’s going to ever be not the identical, but creating a poem, or shifting a rock, or earning a drawing, or fucking with the landscape feels all incredibly a lot the exact,” he suggests. “That act of shifting items around you is pretty significantly akin to the approach of currently being in the studio and painting on a piece of glass. Do you know what I imply?”